A Socratic Homage To Tension

When Jean Jacques Rousseau explained the concept of the General Will, he said that the driving force behind the General Will is the tension created by the sum of the differences in opinion of the members of society. Living in a nation whose social and historical identity is deeply rooted in both biblical and classical tradition, it is important to realize the tension between these two traditions, because it is that tension that is the driving force behind Western thought, and the mixing of those two traditions is so inherent in American culture that most people, if questioned on deeply rooted cultural values, would not be able to distinguish from which tradition a particular belief descended. For example, the Harper’s survey which found a majority of Americans think the central message of The New Testament is “God helps those who help themselves;” a concept much more closely aligned with the classical tradition than it is with the biblical. Taking another classical concept as my mantra, Socrates’ maxim that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” the importance in understanding the tension between biblical and classical tradition (rather than living at the mercy of that tension while being ignorant of it) becomes examining the forces which drive the society to which I belong, and thereby making my life worth living.

Immediately upon deciding to examine the tension between biblical and classical tradition I had to examine what it is that creates tension. Rousseau’s concept of the sum of difference being my starting point, I realized that in order to measure, or even discern difference, there first had to be identified a base of sameness, because in order for tension to exist there must be some sort of fixed base where contact between the two traditions occurs. Think of a rubber band. If at least one end isn’t fixed, no tension can be created and the potential for movement is lost. So it is with biblical and classical tradition in regard to Western consciousness. Tension between the two only exists due to the fact that there are points of sameness, which provide a base from which difference can emerge.

The foremost of these similarities is the belief in a divine. In both biblical and classical tradition, there exists a thinking, reasoning (though not necessarily logical) power set above mankind. Humanity is essentially at the mercy of that power, and existence is a gift granted by that power. At any time, all existence could be snuffed out on a whim. In both biblical and classical tradition, there is always something superior to humanity. In both traditions, upsetting a divine being is a sure path to annihilation. The Sodomites took action which upset YHWH, and he destroyed them. Tantalous took action which upset Zeus, and the curse of the house of Atreus was born. Likewise, finding favor with the divine is a sure path to success in either tradition. Genesis 39:2 is a good illustration of this phenomenon in the biblical tradition, in that the verse starts out by simply stating, “The Lord was with Joseph, and he became a successful man.” Similarly, according to Calasso, in the classical tradition it was Poseidon’s favoring Pelops that allowed him to defeat Oenomaus and marry Hippodameia. So belief in, and dependence upon, the divine is the base from which I see the difference emerge which creates tension between the two traditions.

The emergent differences between biblical and classical tradition are many and varied. Due to temporal and spatial constraints, I shall limit myself to discussion of a central dichotomy which illustrates the tension between the two traditions: that of the attitudinal difference between repentance and defiance, as manifest in a comparison of the reactions of Job and Prometheus after being subjected to torment at the hands of YHWH and Zeus, respectively. Job’s response after suffering at the hands of YHWH is exemplary of the attitude of repentance evident throughout the biblical tradition. Although eventually, after the loss of his property and children, and being stricken with “loathsome sores… from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head,” Job does question God, he ultimately “repents in dust and ashes” (HarperCollins 752-753, 795). This attitude stands in stark contrast to Prometheus in Prometheus Bound who tells Zeus, “You will never win me over with your honeyed words. I will resist you forever, you tyrant” (Aeschylus as cited by Sexson, 2005). In a nutshell, this attitudinal difference is that of theocentric versus anthropocentric moral authority. In the biblical tradition, God decides what is right and wrong. All authority comes from God, and whether an action is right or wrong rests solely on God’s purpose for that action, regardless of whether that purpose is understood by humanity. In the classical tradition, between God and me, I am right. Moral authority rests with the individual. There is no strict mandate for behavior from the divine in the classical tradition, and the gods themselves are often at odds as to what action is right or wrong.

The root of this dichotomy is the tension resulting from the difference in character of the notion of the divine in biblical and classical tradition. In the former, the divine is characterized by omnipotence and benevolence. In the latter, the divine is seen as fallible and indifferent. Despite the inherent differences in the theologies of the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament, the nature of the divine remains similar throughout. God is presented as an all-knowing, all-seeing entity who cares about humanity. All of humanity in the New Testament, as evidenced by Jesus’ commandment to “love each other as I have loved you” (Hunthausen, 2005), and that part of humanity that follows His commands in the Hebrew Scriptures, where God constantly showers favors on His favorites. The benevolence of the biblical God can also clearly be seen in the biblical notion of a paradisal afterlife attained through belief in, and adherence to the precepts of, the biblical concept of God. In stark contrast is the classical tradition, where gods are constantly at odds with humanity and each other, and where, though certain individuals may be favored by one god or another, the mass of humanity is ineffectual to divine beings who rape and kill without reason. Where in the biblical tradition, by following codified rules of behavior one could theoretically be spared the wrath of God, in the classical tradition following the code of one god could lead to one’s rape by another, as in the story of Dionysus’ rape of Aura, whose adherence to a lifestyle in concert with the virtues of Artemis was in part what made Dionysus desire her in the first place.

Examining the tension between the biblical and classical traditions and making an effort to be constantly conscious of that tension as a dynamic, ever-present force in society does make a difference. It allows us to be conscious of the kerygmatic foundations of a society which constantly strives to veil those foundations in favor of constructing a careful, rational worldview at the expense of darkening even further the glass through which, according to Paul, humanity sees the world. This awareness lets us experience a bit of apocalypse and see the world more clearly. Examining the tension between the biblical and classical traditions has helped me lift a veil and see beneath it the cogs driving the machine of culture. To apply Socrates: I have examined life, and made it more worth living.

Works Cited

Calasso, R. (1993). The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony. New York: Knopf.

The HarperCollins Study Bible. (1993) New York: HarperCollins.

Hunthausen, Archbishop R. (2005, October 15) Homily, Bozeman, MT.

Sexson, Dr. M. (2005, November 14). ENGL 212 Class Lecture.

Above is a picture of a blast furnace. The rest of these are in a fairly messed up order due to the blogger uploading posts in some order known only to itself. We'll make it a game. Can you match the caption to the image? oh. I guess I figured out a way to make the captions almost match. or it did in the template. Not the actual blog it seems. So see if you can match them up.

Above is a picture of a blast furnace. The rest of these are in a fairly messed up order due to the blogger uploading posts in some order known only to itself. We'll make it a game. Can you match the caption to the image? oh. I guess I figured out a way to make the captions almost match. or it did in the template. Not the actual blog it seems. So see if you can match them up.

Why does it post these things backwards? Anyway, at right is a cave in Puerto-Rico. I once knew a girl from there.

Why does it post these things backwards? Anyway, at right is a cave in Puerto-Rico. I once knew a girl from there. So, I know we were supposed to google arabesque as an art form, but what is art? Art is certainly music, but this album begs the question, "Is all music art?"

So, I know we were supposed to google arabesque as an art form, but what is art? Art is certainly music, but this album begs the question, "Is all music art?" Sculpture is most definitely art, this sculpture is art within art, as dance is an art.

Sculpture is most definitely art, this sculpture is art within art, as dance is an art.  An odd thing, actually including an example of what was asked for in a post.

An odd thing, actually including an example of what was asked for in a post.  I'm not an expert on ballet, though I do enjoy the ballet (wouldn't know it to look at me, would you?), but this is a nice arabesque.

I'm not an expert on ballet, though I do enjoy the ballet (wouldn't know it to look at me, would you?), but this is a nice arabesque. Jacob's Dream

Jacob's Dream Isaac Blessing Jacob. It doesn't show up to well with the picture being this size, but notice the placement of Jacob's arms. Almost like he's "testifying."

Isaac Blessing Jacob. It doesn't show up to well with the picture being this size, but notice the placement of Jacob's arms. Almost like he's "testifying." The Flaying of Marsyas by Titian. For some reason I've always really liked this painting.

The Flaying of Marsyas by Titian. For some reason I've always really liked this painting. Leda and the Swan. For another artistic rendering, see my first exam.

Leda and the Swan. For another artistic rendering, see my first exam.  The sacrifice of Iphigenia. What we won't do for the winds.

The sacrifice of Iphigenia. What we won't do for the winds.  Another statue of Dionysus. "Wine, women and song." A classical and biblical intersection.

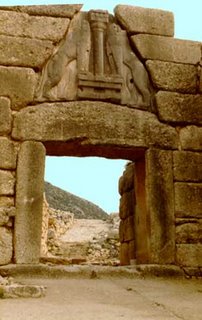

Another statue of Dionysus. "Wine, women and song." A classical and biblical intersection.  The Lion Gate. Supposedly the actual doorjamb to the house of Atreus.

The Lion Gate. Supposedly the actual doorjamb to the house of Atreus.